Entity Clarity Report - Energy in the AI Era: Narrative Control and Capital Legibility

Summary

Energy is not a discovery-driven industry — and that single fact explains why its AI posture diverges sharply from Media and Retail.

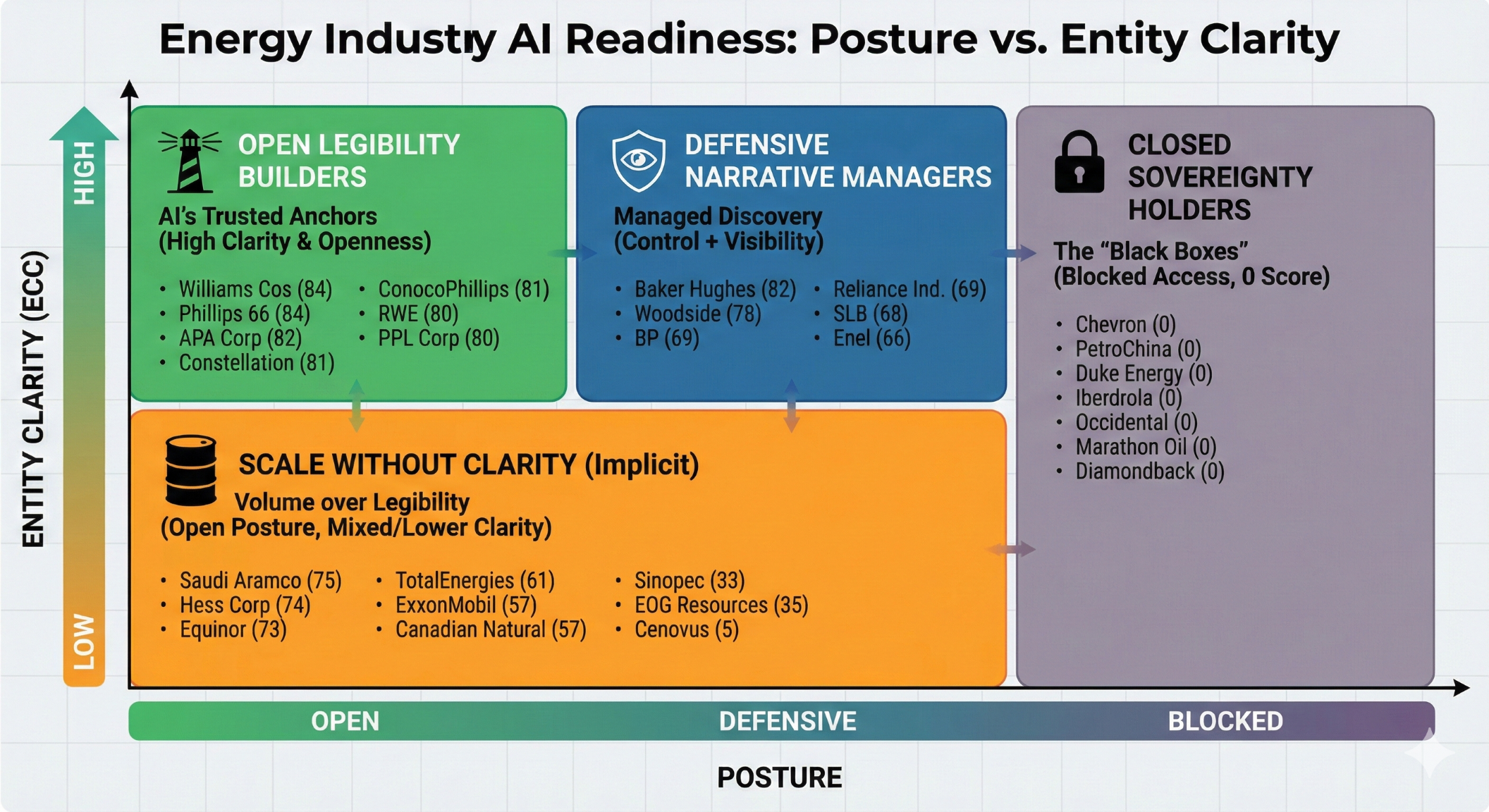

This report examines the global energy sector through the lens of Entity Clarity & Capability (ECC), mapping how energy companies position themselves relative to AI systems that increasingly shape investor perception, regulatory framing, and capital access.

Rather than optimizing for consumer visibility, energy firms are optimizing for AI-mediated judgment. The result is a clear strategic split between legibility builders, defensive narrative managers, and closed sovereignty holders — each reflecting rational responses to the industry’s unique constraints.

Methodology

This analysis applies the Entity Clarity & Capability (ECC) framework to the top 50 global energy companies by market capitalization.

ECC evaluates how legible, trustworthy, and structurally interpretable an entity is to modern AI systems across three weighted tiers:

- Entity Comprehension & Trust (narrative coherence, authority signals)

- Structural Data Fidelity (schema, canonical clarity, internal lattice)

- Page-Level Hygiene (technical consistency, inference efficiency)

Each company is classified by AI Posture:

- Open – Accessible and legible to AI systems

- Defensive – Partially open with controlled narrative exposure

- Blocked – Intentionally opaque or inaccessible

Scores reflect strategic positioning, not moral judgment or operational quality.

Findings

Three core findings emerge:

1. ECC correlates more strongly with capital orientation than size.

Mid-cap infrastructure and utility firms frequently outperform mega-cap oil majors in ECC due to clearer narrative structure and disclosure discipline.

2. Blocking AI is more common — and more rational — in Energy than in Retail.

State-backed, asset-sovereign, or geopolitically sensitive firms often prefer opacity to legibility.

3. Defensive postures represent a temporary equilibrium.

As AI-mediated capital allocation accelerates, partial legibility becomes harder to sustain.

Energy is not resisting AI — it is selectively revealing itself to it.

Landscape

Energy behaves fundamentally differently from consumer-facing industries.

Where Retail optimizes for discovery and Media for authority, Energy optimizes for capital trust, regulatory interpretation, and geopolitical narrative stability. AI systems increasingly act as first-pass analysts — summarizing companies for investors, policymakers, lenders, and institutions.

As a result, energy firms cluster into three distinct strategic archetypes:

- Open Legibility Builders

- Defensive Narrative Managers

- Closed Sovereignty Holders

These archetypes reflect economic realities, not technological sophistication.

Archetypes

1. Open Legibility Builders

“We want to be understood.”

These companies embrace AI interpretation as a feature, not a threat. Their primary audience is institutional capital, not consumers.

- Strategic intent: Reduce misinterpretation risk, improve capital access

- Strengths: Favorable AI summaries, narrative stability

- Weaknesses: Reduced flexibility, greater scrutiny

Examples (High ECC):

ConocoPhillips (81), Williams Companies (84), Phillips 66 (84), RWE (80), Constellation Energy (81), APA (82)

2. Defensive Narrative Managers

“We will engage AI, but carefully.”

These firms allow AI access while managing climate, regulatory, and transition narratives with caution.

- Strategic intent: Preserve optionality and negotiation leverage

- Strengths: Controlled exposure, margin of maneuver

- Weaknesses: ECC ceiling, risk of being framed as evasive

Examples:

BP (69), Enel (66), Reliance (69), Baker Hughes (82), SLB (68), Woodside (78)

3. Closed Sovereignty Holders

“We do not want to be interpreted.”

Typically state-backed or asset-sovereign entities that view AI as a narrative risk.

- Strategic intent: Maintain information sovereignty

- Strengths: Maximum control, reduced activist exposure

- Weaknesses: AI invisibility, exclusion from AI-driven capital narratives

Examples (ECC = 0):

Chevron, PetroChina, Iberdrola, Duke Energy, Occidental, Marathon Oil

Index

Strategic Implications

AI is becoming a default analyst, not a consumer interface, in Energy.

This shifts strategic advantage toward firms that are:

- Easy to summarize accurately

- Difficult to misframe

- Structurally consistent across disclosures

ECC will increasingly influence:

- Capital allocation

- ESG interpretation

- Regulatory sentiment

- Long-term valuation narratives

Opacity buys time — not immunity.

Full Report

Energy’s AI posture is not ideological. It is economic.

Energy firms do not fear AI-driven price comparison or customer substitution. They fear AI-driven narrative lock-in — where a simplified interpretation hardens into regulatory, activist, or capital-market consensus.

Open firms seek legibility to shape that narrative early.

Defensive firms seek balance.

Closed firms rely on sovereignty, protection, or habit.

As AI becomes embedded in institutional workflows, the cost of being misunderstood will exceed the cost of being seen.

ECC measures who understands that trade-off — and who is betting they can avoid it.